As anyone in PR knows, we’re living in a boycott culture. Over Easter weekend Texas congressman Dan Crenshaw (no relation) hopped on the boycott du jour with a video pledging to “throw out every single Bud Light we’ve got.” The punch line comes when Rep. Crenshaw angrily opens his fridge to reveal — no Bud Light at all. “That was easy,” he quips, as he shuts the fridge door.

But the joke might be on Crenshaw. The fridge contains several cans of Karbach, a Houston-based craft brewer that has since 2016 been owned by — you guessed it — Anheuser Busch, Bud Light’s parent company. It’s a pretty common challenge of product boycotts and says something about how useful they are, or aren’t.

Another day, another boycott

For those wondering what the brew-haha is about, conservatives have taken aim at Bud Light (in some cases, literally) for its promotion featuring trans activist and actor Dylan Mulvaney. Twitter is overflowing with posts of angry boycotters pouring out, running over, and even shooting up Bud Light cans in protest. The latest stunt involving a steamroller running over what must be thousands of dollars’ worth of beer, is impressive (though possibly faked). But is the boycott affecting sales? Do product boycotts ever work, or are they performative?

Gauging a boycott’s success depends on its goals, naturally. In this case, anger seems channeled into hurting Bud Light sales and/or forcing it to end the Mulvaney partnership. So far, there’s some evidence that sales might have been affected. According to Beer Business Daily, “it appears likely Bud Light took a volume hit in some markets over the holiday weekend.” Yet BBD notes it has limited data from mostly rural Midwestern and Southern distributors. After days of silence, Bud Light released a statement defending the Mulvaney promotion, but it has been relatively quiet throughout the storm.

When product boycotts trigger “buycotts”

Product boycotts are usually more complicated than they seem. A case in point — Kellogg business school professor Anna Tuchman analyzed the outcome of the 2020 boycott of Goya Foods by Hispanic leaders. It all started when Goya’s CEO praised then-President Trump’s immigration policy. Yet calls for a boycott of Goya products quickly drew a backlash among Trump supporters. Tuchman studied supermarket data and found that the backlash actually raised sales, albeit temporarily. She theorized that, unlike the seven percent of U.S. households that were already regular Goya customers and could potentially boycott the brand, nearly anyone could decide to buy it in solidarity. Many did.

Goya’s more narrow customer base makes it different from a mainstream brand like Bud Light. But the same principle could well apply here. Even if the boycott keeps conservatives from buying it, the PR and social media coverage could invite a “buycott” of Bud Light from others, just as it did for Goya. Then there’s the problem Rep. Crenshaw ran into; Bud’s parent company Anheuser Busch owns more than 500 beer brands, including many that are popular in the U.S., from Stella Artois and Michelob to Corona and Blue Point. So, avoiding all A-B brands might take some homework by the boycotters.

Brand social status is a key factor

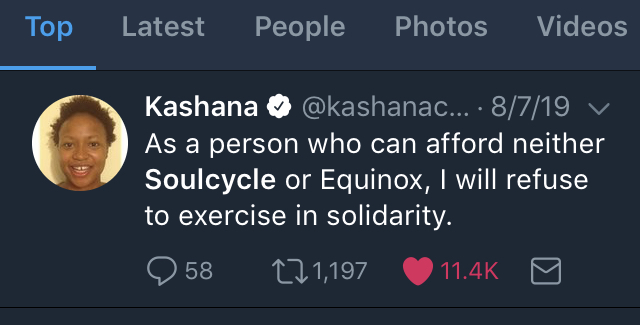

Another factor that affects a boycott’s power is a brand’s strength as a cultural signifier. This should be obvious, but it’s often overlooked. Someone’s choice of black beans isn’t a status symbol. It’s not something they brag about or see as part of their social identity. Yet lifestyle brands do act as badges of identity, so they’re more vulnerable to protests. A 2019 boycott of Equinox and sister brand Soul Cycle (over billionaire owner Stephen Ross’s Trump fundraiser) hurt class enrollment rather decisively for both brands. The reason? Both enjoy a carefully cultivated image of social responsibility and inclusion. They’re a signal of status for members, so during a celebrity-led boycott, no one wanted to rave about their Equinox Cardio Sculpt instructor on Instagram or post about the latest Soul Cycle swag. Lots skipped their workouts altogether.

I’m not sure where beer fits on the social status scale, but I’d say it’s a stronger signifier than beans, if maybe lower than luxury fitness. Perhaps more importantly for a 30-year-old product like Bud Light, it needs to expand its appeal to add new drinkers, like younger people and women. Its Director of Marketing, Alissa Heinerschied, put it bluntly in a March interview. “I had a really clear job to do when I took over Bud Light…this brand is in decline. It has been in decline for a very long time. And if we do not attract young drinkers to come and drink this brand, there will be no future for Bud Light,” she said.

Finally, the LBGTQ market is a huge and spendy one. Beer brands have shown their support in the form of splashy Pride sponsorships, targeted advertising, and influencer campaigns for years. Those steamrolling the brand will have a hard time choosing another beer that hasn’t supported the gay and trans communities.

If the Bud Light boycotters’ aim is to grow awareness of their position and build community among like-minded people, they have succeeded. The brand is being trashed in every corner of the web, and that’s not helpful to its marketing team. But if the goal is to put the brand out of business, or push it and other beer makers to pull LBGTQ support and sponsorships, it will most likely fall flat.