In a move that surprised no one, embattled CNN CEO Chris Licht stepped down yesterday. Media-watchers were taking bets on how long Licht could last after a “brutal” and deeply reported profile in The Atlantic. The piece highlighted his controversial year at the helm and was punctuated by the widely criticized decision to televise a town hall with Donald Trump in front of an “extra-Trumpy” live audience.

The post-mortem on Licht’s brief tenure will continue, but I’m more interested in the strategy behind the decision to give The Atlantic’s star reporter Tim Alberta full access for a profile. Word is that two senior CNN communications executives are also casualties of Licht’s fall. Matt Dornic, a 12-year CNN veteran who was also featured in The Atlantic piece, has reportedly left, along with Kris Coratti Kelly, who was brought in by the new CEO only a year ago.

Nicholas Carlson of Insider puts it this way:

I guess the lesson is: when your boss is about to do something really stupid, throw your body in the way. Even if he’s your new boss and seems really obsessed. One, two, three – JUMP – right in their way. Make them walk around your wiggling carcass on the floor. Throw a leg up if they try to go over you.

When to give media full access to the boss

It’s the inside version of “Fire the agency!” But can an internal PR team prevent bad media relations decisions? It’s impossible to know whose idea it was for Licht to sit down with Alberta, but it’s unlikely to have come from the PR team. That kind of access isn’t what you advise when a CEO is mired in controversy, or if his status is uncertain. It’s the kind of profile you want when a business leader is at the peak of popularity or influence.

Full access may also be advisable when a popular founder or CEO embarks on a comeback plan or announces a new venture – think Howard Schultz returning to Starbucks, or Bob Iger coming home to Disney to save the day. Each was a situation where a largely popular and successful leader moved to consolidate support in the face of a challenge.

Licht’s situation was different. He was a newcomer without a base of support. Moreover, he ruffled feathers from the beginning, and the Atlantic feature only emphasized his isolation from his own team. My bet is that he was haunted by the reputation of his popular predecessor Jeff Zucker, and so eager to differentiate himself from Zucker, that he wanted to cement his own reputation with the article.

Who takes the blame for bad PR?

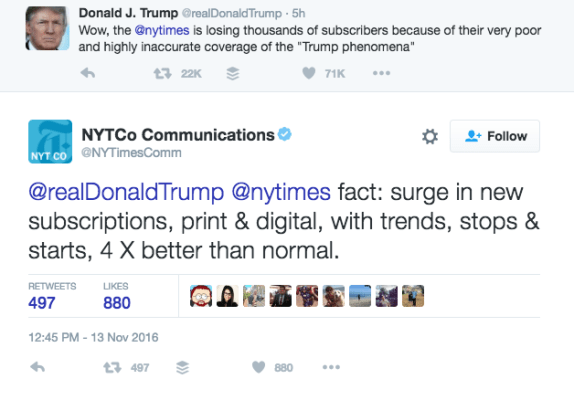

The blame-the-PR-guy reflex isn’t limited to CNN. Government officials often talk about the need to “tell our story better.” And most PR professionals have known a client who’s in denial — about his organization’s problems, his own reputation, or just reality in general. It’s a challenging and self-defeating situation. Most insidious are those who know the truth but hide it from their communications staff – and themselves. PR pros aren’t magicians, and denial is a dangerous state for a chief executive or public personality.

Clients deserve the truth, but what if they can’t handle it?

We once won a PR and reputation engagement from a company that suffered from harsh online reviews, among other challenges. A little research showed that its customers’ anger was understandable. Our proposal made it clear that if the company didn’t change its practices, our work would be wasted. When the client called to say we’d won the assignment, he said we were up against three digital marketing companies who recommended SEO. “You were the only one who told the truth,” he said.

Sadly, that situation was unusual. A company or executive that’s in denial is impossible to help. “Good PR” isn’t just the result of skilled communications or media relationships; it needs to have a basis in reality.

When in doubt, fire the PR team

So, does the PR team deserve to go down with their captain? Some might say so. It’s not unusual for senior lieutenants to follow their chief out the door. After a rough patch it can be a useful signal that the organization has turned the page. In this case, Dornic must have known the story was becoming an exposé. That was apparent from the tenor of Alberta’s questions and his own warnings to Licht about what his staff was saying about his leadership.

Yet the CNN situation seems like a case of blaming the PR team for a year’s worth of missteps. Dornic in particular tries to soften Licht’s remarks in the profile. He clearly knew the boss was in dangerous territory. Another problem was timing; the article was months in the making. What may have started out on a positive note grew perilous as the newish CEO opened up in an unfiltered and tone-deaf way. But at that point, it would also be risky to pull access because you’d have even less control over the process.

In most cases, the internal comms team can’t countermand a CEO who’s bent on opening up to the press. A PR adviser can recommend, warn, and prepare. They can do their best to rebut rumors and challenge misconceptions, but background sources are impossible to confront directly. It was an asymmetric struggle from the start.

If the CNN PR team is to blame for anything, it could be for failing to sense what was coming, and to brace for impact.