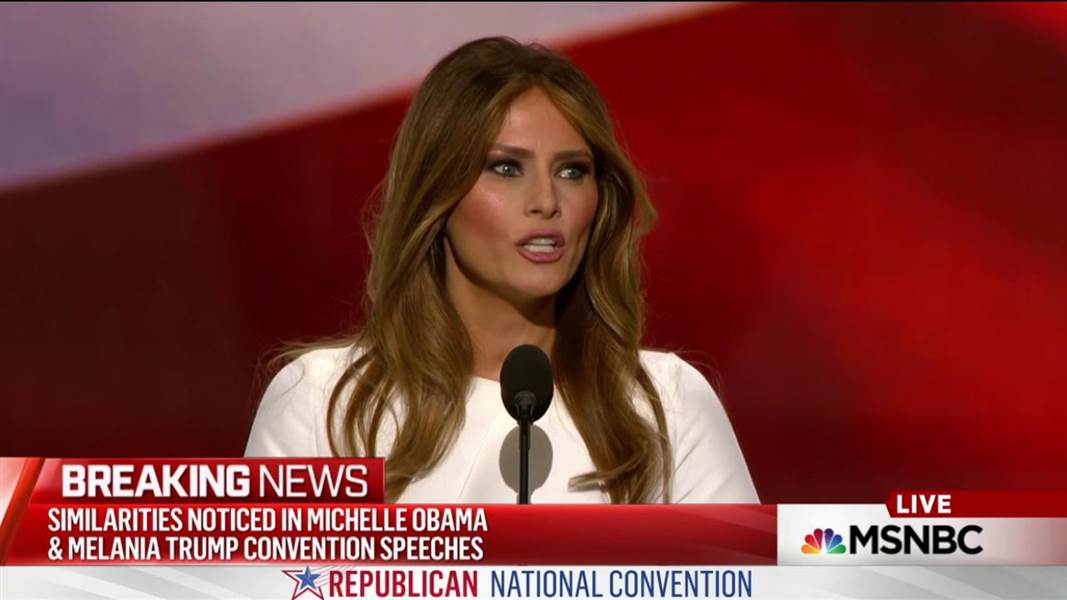

This week the Trump campaign and the Republican National Convention reminded the PR community — and everyone else — of the perils of mishandling a public mistake. Within an hour of what should have been the high point of a shaky first day for the RNC, the campaign was in full damage control mode. Melania Trump’s primetime address, which had been carefully orchestrated to “humanize” her husband, was found to contain language lifted from Michelle Obama’s 2008 DNC speech.

It didn’t take long for social media to erupt in flames. Twitter featured damning videos of Ms. Trump and Ms. Obama speaking side-by-side, using nearly identical language. Mocking hashtags like #FamousMelaniaTrumpQuotes featuring iconic historical quotes were everywhere. Speech-gate quickly trickled up to “traditional” press, dominating the news cycle on Tuesday.

The mistake was bizarre and the resulting coverage inevitable. But what made it infinitely worse was the campaign’s response, led by Paul Manafort. Manafort insisted – despite visual evidence – that there was no plagiarism and that the accusations were dreamed up by a jealous Hillary Clinton. That lasted about 32 hours, until today, when the Trump organization released a statement from a previously unknown writer who took responsibility for the mistake. The statement extended the story, but now that a (somewhat) more coherent explanation is out, it will probably be put to rest, unless there is more to the saga.

Freakish as it was, the entire episode is instructive. It’s a pretty fair guide for what not to do if you break a rule or make a public mistake. Here’s what they should have done instead, and how it applies to other situations.

Rule one: Acknowledge the mistake. In this case, the failure to admit error was probably driven by Trump himself, but a PR heavyweight like Manafort should have known better than to deny the obvious. Claiming the similarity was a coincidence didn’t just destroy the campaign’s credibility. It also made the press mad, feeding their determination to get satisfaction. Check out a visibly frustrated Chris Cuomo’s interview with Manafort here. It’s seven minutes of a truly extraordinary tug-of-war that Manafort is just not going to win.

Rule two: Where necessary, explain. Reasons aren’t always required, and some mistakes are compounded by complicated explanations, which can sound like excuses. But in this case, a semi-feasible rationale was required. It wouldn’t have been hard. All the campaign had to say was something like, “As an aide was helping Ms. Trump polish her remarks, some language from the writer’s notes on previous convention speeches were inadvertently included in the final draft.” Maybe not 100% airtight, maybe not even true, but good enough to offer respectable cover.

Rule three: Apologize. Make it sincere, credible, and unselfish. Focus on the damage done or persons offended, not on the one who committed the error. Again, Trump is not a guy to issue a mea culpa, but the reluctance to do so here drove the story into overtime. People make mistakes, and the public loves to forgive. In this case, where the real victim was Melania Trump and not her husband, it would have been PR-savvy (and shown common sense) to include a brief expression of regret to the public explanation of how the speech contained material not original to the writers.

Rule four: Accept blame. Don’t point fingers, deflect, or try to blame someone else. Acceptance of responsibility is the foundation of a sincere apology. Contrary to what some may think, it’s a sign of strength, not weakness. Manafort’s attempts to connect the mini-scandal to Hillary Clinton just weren’t credible. They infuriated the media and gave the Clinton campaign fresh material to include in their fundraising emails.

Rule five: Fix the problem. In most cases a business or individual will announce a fix as a way of assuring that the error won’t recur. The company recalls its faulty product, settles a lawsuit, or changes its policy. Maybe the celebrity checks into rehab to receive treatment. In the case of speech-gate, this isn’t vital because a fresh mistake would only harm the campaign, not the public. But the Trump team would do themselves a favor by adding more communications infrastructure, including the typical vetting process that should accompany any public remarks.

Overall, the Trump campaign’s handling of the situation, from the speech itself, to the stonewalling and spinning and eventual admission of a problem, reeks of an amateur operation. In politics, as in PR, it pays to have professionals on the job when the stakes are high.