The #metoo movement has claimed the reputations of many high-profile men. But its real impact may be at the corporate level. Our heightened awareness – and the corporate reluctance to address systemic misbehavior – presents serious public relations challenges for established companies in every sector. No brand is immune from a reckoning with the consequences of inattention to sexual harassment and inequality in the workplace.

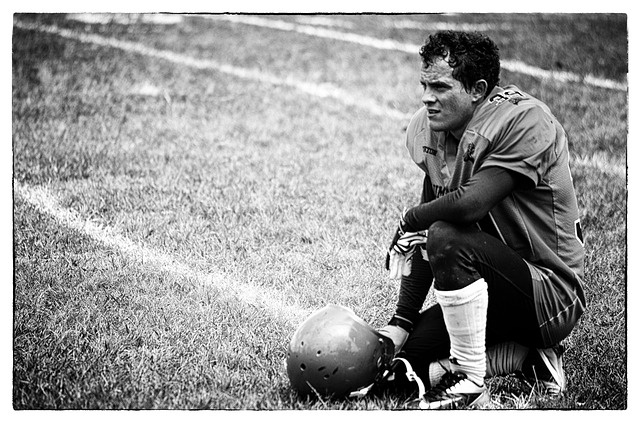

Take onetime media darling Under Armour. The brand enjoyed huge early success, in part due to the real-life story of founder Kevin Plank. A former football team captain, Plank developed the line based on moisture-wicking technology that was later adopted by NFL teams and featured in hit movies. The company expanded aggressively, and with its growth came inevitable setbacks. The past two years have been particularly rough, and its fumbles show how hard it can be to salvage a reputation when faced with simultaneous business challenges.

The reputation issues started with Plank’s public praise of President Trump as a “pro-business leader” last year. The comment didn’t sit well with some of the brand’s star athletes like Stephen Curry and Misty Copeland, and customers threatened a boycott. Plank was forced to explain himself in a full-page ad in hometown paper Baltimore Sun. He later resigned from the president’s Manufacturing Jobs Initiative Council and joined other business leaders in condemning Trump’s equivocal comments after events in Charlottesville – which prompted threats from Trump supporters. Things eventually calmed down, although the business environment didn’t improve much.

Business suffered as some of its large retail customers struggled, and the brand lost cachet among the all-important teen segment. Earlier this year Under Armour announced a restructuring meant to streamline its business and refocus on women’s apparel, among other areas. Yet just as its recovery started to gain traction,it was hit with serious criticisms of workplace behavior and culture born out of #metoo.

A scathing story in The Wall Street Journal recounted how female employees were subjected to sexual harassment and “inappropriate conduct” in the workplace. Under Armour covered expenses for employee entertainment at strip club, and the piece describes an annual outing at Plank’s home where young female employees were invited based on their attractiveness.

To its credit, the company responded quickly in the wake of the Journal story. Plank’s statement referred to “systemic inequality in the global workplace” and pledged to “accelerate the ongoing meaningful cultural transformation that is already under way at Under Armour.” Although the statement doesn’t actually accept responsibility for misbehavior, it does promise to do better.

Yet the Under Armour example shows how, when a company is already weakened, a reputation shakeup can do more damage than it otherwise would, precipitating customer disenchantment and defections of talent. By contrast, Nike announced a raft of departures by highly placed male officers after scores of female executives complained of systemic harassment, unfair treatment, and retaliation when they brought their concerns to HR officers. But the $112 billion Nike may be better equipped to withstand setbacks, and it has moved swiftly to install women in senior leadership positions.

The formula to protect reputation in the #metoo era is both simple and very, very difficult.

Root out the bad actors

This is an obvious first step, though it can be easier said than done when the harassers are considered top performers, or if they have a close relationship to the CEO. One of Under Armour’s earliest employees was Scott Plank, Kevin Plank’s brother, who rose to EVP for Business Development but retired quietly in 2012 amid allegations of sexual misconduct. Many other positions were held by friends of the founder, and, not surprisingly, it had a corrosive effect on the culture.

Make sure women are in positions of influence

Workplace studies show that harassment is more common where men outnumber women and where the supervisor ranks are mostly male. Research by the American Psychological Association (APA) showed that sexual harassment at work is more likely to be reported at organizations with women in senior leadership (by 56% vs 39%). Under Armour’s only C-level female was the HR chief, and she recently left the company to accept another position. Over the past year the company also lost its female SVPs for global retail and global brand management. If those aren’t flashing red lights, I don’t know what is.

Establish a rigorous protocol for complaints

Too many corporations limit their role to refreshing the corporate sexual harassment policy or stepping up worksite sessions on the topic. They may talk the talk, but when a sensitive complaint surfaces, the impulse is to cover it up. Worse, the corporation may stigmatize the person who brought the complaint, sometimes unwittingly. To protect its reputation a corporation cannot afford to ignore systemic power imbalances, unresolved complaints, or episodic misconduct.

The heart of reputation, of course, is corporate culture. David Ballard, Assistant Executive Director of Organizational Excellence at the APA sums it up. “All the training, policies and punishments won’t have an impact on harassment if you don’t address power differentials, pay equity and gender equality in organizations,” he notes. Like most workplace problems, the #metoo affliction is easier and less painful to prevent than it is to treat. An organization that cultivates diversity, openness, and ethical behavior is in far better shape to handle unforced errors of any kind, especially today.