There’s not a major corporation today that doesn’t have a small army of PR and reputation experts helping it navigate a tricky media and government relations landscape. But occasionally, the damage comes from a company’s own ranks.

That happened this week when the Campbell Soup Company found itself in hot water after a bizarre tweet from its own head of government affairs — an executive who ironically lists “crisis management” among his skills. It all started when Campbell VP Kelly Johnston tweeted about the so-called “caravan” of immigrants traveling north from Honduras. Mr. Johnston posted a photo of the migrants along with a claim that the George Soros-backed Open Society Foundation is an organizer of the group, including “where they defecate.”

Blech. There’s no evidence that Mr. Soros or his foundation has any connection to the migrant march. The Open Society quickly posted a denial, expressing that it was “surprised to see a Campbell’s Soup executive spreading false stories.” Johnston deleted the tweet and later shut down his Twitter account, but not before sharp-eyed @kenvogel of The New York Times captured it in a screen shot.

Bad timing compounds a mistake

Kelly Johnston has a background in politics; he’s a former Secretary of the U.S. Senate – not an unusual pedigree for a Public Affairs VP. But surely a top government relations officer should know better than to publicly dabble in conspiracies that simmer in the dark corners of the interwebs. And Johnston’s tasteless tweet couldn’t have come at a more sensitive time for Campbell.

First, Mr. Soros is a frequent target of anti-Semites and among several prominent persons targeted in a series of pipe bombs delivered by mail this week. Mr. Johnston’s tweet was posted Monday, and he likely didn’t know about the mail bomb, but the timing is terrible.

What’s more, it comes as the company is under pressure from shareholders. Campbell has been plagued with poor earnings and faces a challenge by activist investor Bill Loeb. A consumer boycott of Campbell’s many brands due to a tweet by a “soup Nazi”(as one critic dubbed Johnston), is a recipe for more than heartburn. And it scalds worse given that Campbell’s soup is an iconic brand long associated with home and hearth.

So, what’s a company to do when the call is coming from inside the house? Campbell did take several proactive steps in this case.

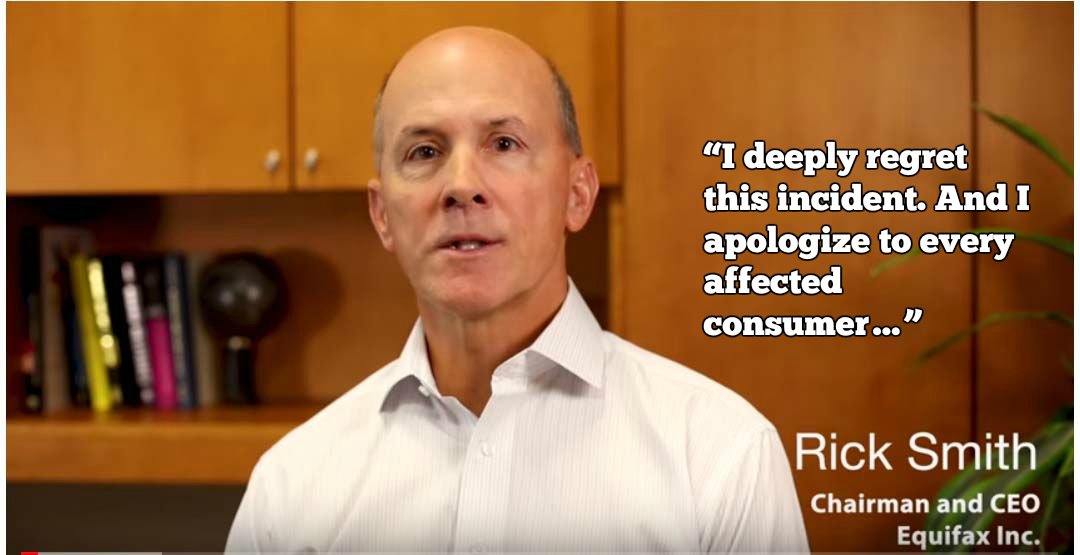

Issue a clear and quick response

Shortly after the backlash to Johnston’s tweet, Campbell posted a tweet of its own distancing the company from Johnston’s comment. “The opinions Mr. Johnston expresses on Twitter are his individual views and do not represent the position of Campbell Soup Company,” it tweeted. The comment itself wasn’t enough, and Vogel doggedly tweeted follow-up questions to Campbell, but it was a start.

Apologize to the offended party

Campbell took pains to contact the Open Society Foundation as the controversy reached a boil. In a letter from interim CEO Keith McLoughlin, the company expressed that Johnston’s comments “are inconsistent with how Campbell approaches public debate.” A bit stilted, and the response falls short of an apology.

Remove the problem if possible

This is the stickiest issue for many companies. Dismissing an executive for speaking out can fix the problem, but it can also create additional negative coverage or precipitate litigation in some cases. But yesterday we learned that Johnston will retire from the company in early November, and that news was also included in the letter to the Open Society Foundation. In response to media inquiries, the retirement was positioned as something that had been planned all along, although that seems unlikely.

Make your values clear

This is the most important part of protecting a corporation from reputation damage that starts inside. Most companies have a written social media policy, but any executive of Johnston’s rank should be empowered to tweet or post on its behalf where news or issues warrant. What’s more powerful is a clear statement of values, backed and lived out by the organization itself.

seems defensive in doing so. Tesla goes on to

seems defensive in doing so. Tesla goes on to  After an emergency landing in which a passenger was killed on April 17, Southwest released an initial statement on social media and its press page saying it was gathering information about the situation. Unlike Tesla, Southwest made the simple acknowledgement, showing that the situation had its attention and showing concern for loved ones seeking information. The

After an emergency landing in which a passenger was killed on April 17, Southwest released an initial statement on social media and its press page saying it was gathering information about the situation. Unlike Tesla, Southwest made the simple acknowledgement, showing that the situation had its attention and showing concern for loved ones seeking information. The